Forever Viet Nam

This Veteran’s Day we remember the lives of the millions of fathers, mothers, sons and daughters, brothers and sisters, all over the world, lost to the heinous pursuit of War, Inc.

During a recent, week-long visit in Seattle, I walked downtown from my sister’s ungentrified-as-of-yet Capitol Hill apartment to the Pike Place Market. I caught up with an old friend and bought his recent publication, entitled, Visionary Surrealism at the Pike Place Market. He had customers lining up, so I moseyed past the food and craft stalls to the outdoor deck overlooking Elliott Bay and the harbor piers.

The City of Seattle is building a viaduct tunnel on Alaskan Way to divert traffic in order to allow more pedestrian access to the waterfront. While looking down upon the construction site I heard a voice sidle up next to me, asking if I knew “What’s going on over there?”

The voice belonged to a young Asian man, in his early twenties, I surmised. I answered something whimsical, like “Progress.” He laughed. He introduced himself as a first time visitor to Seattle from Bellingham, where he was enrolled as a student in a college. He spoke English perfectly well. I shared my name and asked him what country he grew up in. “Viet Nam.” I sucked in a breath.

I have a habit of apologizing to people I meet from war-ravaged countries who have suffered, or are presently suffering, grave injustices forced upon them by profit-driven US imperialism. (I recall apologizing to an Iraqi in Aukland as we were both trying to cross a busy, four-lane street. We held hands, and took off running.)

This young man listened politely as I made awkward amends for the folly of War, including an anti-government mini-rant. He seemed astonished at this impassioned spew forthcoming from a random stranger, and took a beat to remark, “Wow. I’ve never talked to an American hippie before.”

True, I looked the part, with long curly blonde locks, wearing a colorful patchwork quilt of a flowing skirt, a jean jacket, and a leopard-print beret. Plus my glasses were rose-tinted. I smiled at his retort. “Well, I was born about ten years too late for that party, but I’ve done some catching up since!” I asked him if he was familiar with punk rock, as that was my jam (social identity) at eighteen, in this very city.

“Punks and hippies shared a lot in common,” I went on, “we lived in communal houses, created a unique music and cultural scene, and existed outside society. Intentionally. Politically aware and anti-War.” In a softer tone I asked, “Were you much affected by the War?”

He answered that he was not personally, but that his parents’ lives had been greatly impacted. Their agriculturally-subsistent families had been forced to flee their villages, and for many years, never had enough to eat. “It ruined their Life,” he admitted. His parents were poor and hard-working, making sacrifices in order to afford a better future for their son, to be able to send him to the U.S. for an education. To the country that robbed them of their childhood.

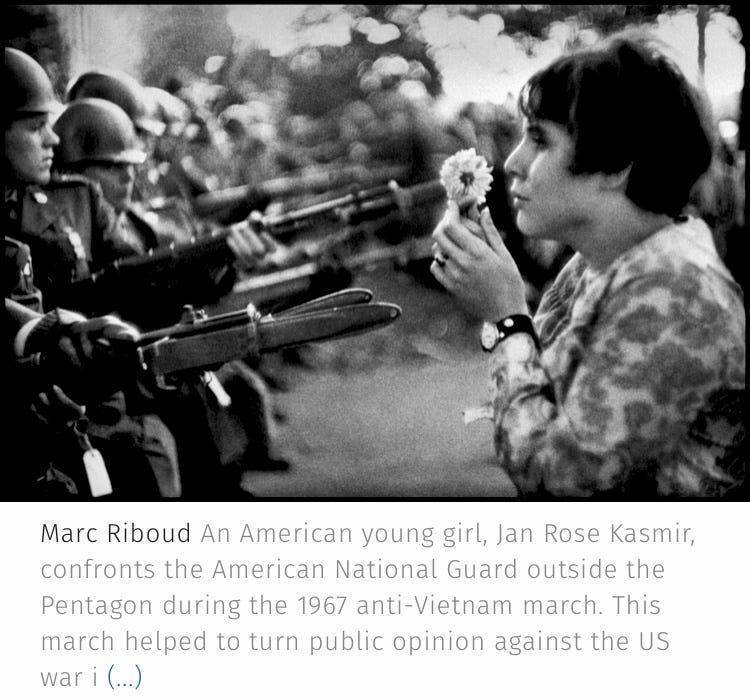

I asked if he had any idea of the extent of the Anti-Viet Nam War Movement in the U.S. in the Sixties. “There were marches, sit-ins, and demonstrations all over the country. Huge protests. There’s tons of books and films about it.” I wanted to convince him of our collective struggle and regret. He seemed open to hearing about it.

“People were arrested for dodging the draft, and being conscientious objectors! Many left the country. Men that served came back and burnt or threw away their medals in public.”My fervor was rising; he looked wide-eyed and incredulous. “I live with radical Socialists, people who have been organizing against the CIA’s Propaganda Wars their whole life.”

At this point I was not going to mention death tolls, body counts, body bags, Agent Orange, or that the Washington administration had been consistently advised the twenty year-long war was unwinnable, for years before it officially ended in 1975. Or that over 100,000 Vietnamese were killed by exploding ordnance in the years following the war.

He was deep in thought, surprised, perhaps he never imagined hundreds of thousands of Americans had taken an active role in condemning the War. He asked, “Do they still think of us now, after all this has been over for so long?” I nearly cried. I searched for some personal anecdote to show him it was true that we cared.

“My Lai,” I whispered. He corrected my pronunciation, “Me lie.” I related I was twelve years old when Lt. Calley’s highly publicized trial for the massacre took place. At that young age, it was one of the worst crimes of humanity I had ever contemplated, and had filled me with acute depression, grief, and sorrow. (Soon after, I found The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich on my Dad’s bookshelves).

“People were shocked and outraged hearing about My Lai. They filled the streets. It turned the whole narrative about the War around.” The awful truth had finally descended on everyone. “We knew My Lai wasn’t an isolated incident.” My new friend acknowledged this with a nod.

At this point, we needed something to lighten the mood. He asked if I could teach him some hippie slang. Er…ok! Kinda cheesy…….well, here goes…”Far-out!,” “Cool,” Outta Sight!,” “Groovy.”

He asked, “Please explain, “Groovy.” I thought of the Sixties song by Simon and Garfunkel, “Feelin’ Groovy”, and answered, “It’s like feeling good vibrations, having a sense of Oneness with the Universe and All Beings, mellow, psychedelic…”Groovy!””

He couldn’t resist teasing, “So, would you say the Americans in Viet Nam were “Groovy?”” “Maybe if they were on LSD,” I muttered. “No, the American presence in Viet Nam was NOT “Groovy.””

I paused to consider if I possessed any other nuggets of hard-earned wisdom to leave this inquisitive young man, who had endeared himself to me in an unexpected way. Ahhhh….”There’s a saying in common parlance these days, generally agreed upon to be true -

“The hippies were right.”

I let it sink in before continuing, “In regards to a lot, in fact - living lightly, in harmony with the Earth, promoting natural foods and medicine, using psychoactive plants, uniting with Indigenous Peoples, sharing resources communally, and most of all, in proclaiming, “Make Love, Not War!””

It had been an energetic and memorable conversation. He asked for a photograph of us together. We cozied up and I flashed the peace sign. “Show your parents,” I said. We parted with a hug.

I believe i blew his mind, and being called upon to represent a very potent chapter of enlightened hippiedom had certainly blown mine.

The hippies were right.

Note: I read Seymour Hersh’s 1971-72 articles about My Lai, as well the one he published in 2015 in the New Yorker after his first return to the village. My Lai is now visited by thousands of tourists a year, and hosts the My Lai Museum, which honors the 504 victims and holds commemorative ceremonies on the March 16th anniversary.

Many veterans have returned, seeking peace and forgiveness, and to volunteer in Agent Orange action groups, which invoke International Aid to remediate damages done to the Vietnamese people and their environment by the defoliant.