Viet Nam Plus 50

"The War is over," said John Lennon, a little bit prematurely. But peace was our fervent dream from the Sixties until April 30, 1975, when it was truly, really over.

The American death toll was 58,220 and the death toll of the Vietnamese was more that 800,000. Perhaps more than a million.

But more was lost than that. We lost a president and a progressive government. It wasn’t the only reason JFK was murdered, but it was one of the reasons. The military wanted the war. The oligarchs wanted the war. The veterans of World War II thought sending their kids off to war was a “Rite of passage.” And when it began, a great many young toughs were “gung ho” (words they learned once they got there). They could prove themselves by killing people of another race.

President Lyndon Johnson, who may have had a role in JFK’s assassination, jumped at the chance to be known as a war-time president. His first official act was reversing Kennedy’s Executive Order pulling American advisors out of the killing fields. Johnson went whole hog. He kept the advisors in Viet Nam and added half a million soldiers to the little country.

The war backfired on the U.S. The soldiers, who wanted to “kill a gook,” ended up realizing that their enemies were just like them. Some white soldiers who had been racist before the war ended up with best friends who were Black or Latino. This added to their confusion, especially when they came back on leave or when they were discharged. Not even their hometowns were the same any more. They began to understand that they had been used by the power structure to play a geopolitical game with the Soviet Union and China.

Unfortunately, the establishment wouldn’t leave them alone. The propaganda was ceaseless. The CIA was busy becoming drug dealers in the former French colony and the neighboring Golden Triangle. They even had their own airline, Air America, which made it convenient for them to ferry heroin back to the U.S. to be injested by ghetto people and newly returned soldiers. The CIA made a great deal of non-accountable walking around money. So much, in fact, that they repeated their capitalist enterprise a few years later with tons of cocaine which the Nicaraguan Contras gave to the CIA in exchange for weapons. The CIA then dumped it on the segregated streets of South Central Los Angeles (See Gary Webb’s, Dark Alliance, for more about that fiasco.)

But most soldiers, while in the Nam, were stuffing their duffle bags full of some very fine marijuana and bringing it home with them. The pot kept them from waking up screaming at night as their minds relived the killings they had just endured. Now that we’re 50 years down the line there is less screaming and more sorrow about the whole experience.

Most vets are ok, most of the time. But there are triggers. It might be something as simple as hearing Marvin Gaye’s voice on the radio, or that song “Don’t Give Up,” by Peter Gabriel and Kate Bush. For some vets, it’s an endless night where the Sun never comes out. It starts with illnesses from Agent Orange, the chemical that defoliated much of Vietnam, or just the inability to socialize with others. Most of the time, we’re alright. But there are times when we’re triggered. For instance, having the wrong reaction to the murder on a New York street of CEO Brian Thompson by Luigi Mangione. Luigi is too young to have been in Viet Nam, but he lives in the country whose illness was created by the war. None of us want to be part of that, but we feel shame when we confront ourselves about the random murders that surround us and how little they mean to us.

Drugs, Fragging, Fighting the Cong, and the Apocalypse

Meanwhile, back in the Nam, it was hard times for many 1st and 2nd lieutenants. The ones who treated their troops badly had to keep looking behind themselves because fragging (being shot by their own troops) was a constant fear. In that war, fragging was an equalizer. Many of the officers, especially the arrogant and racist, would end up as casualities of war, who were listed as having been killed in action. The high command didn’t care much about what happened to their junior officers in the field, as long as they could report lots of enemy kills to headquarters.

After 10 years of a war that the U.S. was losing, a lot of American soldiers had been rotated in and out of Viet Nam. Those who got caught up in a draft were in for two years, while enlistees spent three years where they didn’t want to be. The military learned that people who were drafted made lousy soldiers. Conscription had begun in 1940, as the U.S. geared up for World War II, and ended in 1973. It would have ended in 1971, but Nixon got Congress to approve a two-year extension. There has been no draft since then.

In 1968, I was stationed at Fort Gordon, Georgia, counting the days until I would be free of the Army. I hated the Army but liked many of the soldiers. We all hated the Army and we all had countdown lists marking off the days until we could go home.

Then one day our CO (Commanding Officer) told up to prepare to move into Washington DC to maintain order during a giant peace march. There were at least 20,000 soldiers on the base. “And you’re telling me they will send us all to DC to do what? To kill peace marchers? We’re not going for it.”

And so it went. No one in that mass of humanity was “going for it.” That night was deathly still on the base. No one needed to argue the issue. We were not going to DC. There was no sign of any officers walking around the base that night. We guessed that they had a lot to talk about. Our friends on other bases were like-minded. Everyone had had enough. The day of the Peace March came and went. We went nowhere. No one ordered us not to go. They just knew better.

It was around that time that Nixon must have gotten reports that the troops, his troops, were in a foul mood. The oligarchs, the Top Brass and the politicians had pushed it so far that they no longer had a reliable Army. It took a few months to acknowledge that the Viet Nam war was lost. The best thing for our rulers to do was demobilize the military as quickly as possible. Our soldiers in Viet Nam had been beaten by a small Southeast Asian country during Viet Nam’s Tet offensive, earlier that year. And then, our “great Army,” virtually called it quits. Nixon’s troop withdrawl started soon after, and by the official end of the war on April 30, 1975, there were few American soldiers left on dry land. Most of the military in the vicinity were the Navy, which were safely offshore, where they would be needed to bring Vietnamese collaborators to the USA.

What was at stake in the Viet Nam War?

The Vietnamese, led by Ho Chi Minh, forced the French to leave the country. It was the first victory of a poor country from the Global South over a former colonial power. Since 1858, France had ruled over Indochina, which was comprised of Viet Nam, Laos and Cambodia. In 1954, the Viet Minh forces surrounded the French army at Dien Bien Phu. As a result, Viet Nam was split at the 17th parallel. The French asked the Americans for help, hoping to regain their colony.

When LBJ sent troops to Viet Nam, it responded by expanding the North Viet Nam army (NVA) and calling for volunteers to fight the invaders in the South, who were called the Viet Cong. Most of the ground fighting took place in the mid-section of the country, the Mekong Delta and the major city, Saigon. However, when Nixon increased the bombing, it was targeted at the capital, Hanoi, in the North. Many of the flight bombers were shot down. In the U.S., they were hailed as heroes, while to the people on the ground, they were considered murderers and were imprisoned, but ultimately returned to the U.S.

The hopes of a U.S. victory were dashed by the Tet Uprising, in which thousands of Vietnamese, including civilians, rose-up in the former Imperial capital of Hue. The Vietnamese seized the city and strenthened their military forces. While the war lingered on for a few years, it was the end of the possibility of a U.S. victory.

U.S. troops began to be reduced, as the Vietnamese expanded the regions that they held. By April 1975, it was all over. NVA tanks began rolling into Saigon. The official residence of the South Viet Nam puppet president was put under fire and the few servants still in the building raised a flag of surrender.

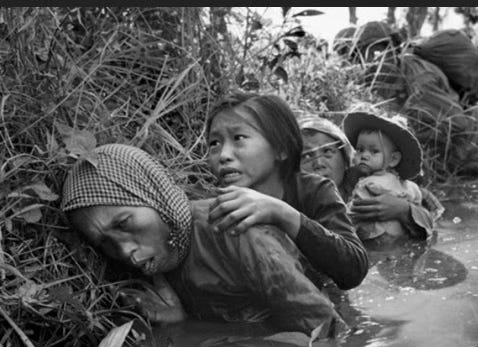

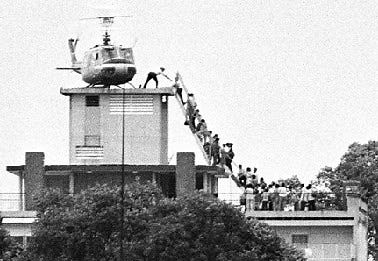

Meanwhile, those who had collaborated became desperate to leave the country. Many were termed the “boat people” since they had filled so many boats of all kinds to get into international waters where the U.S. Navy picked them up. The higher-up collaboraters tried to escape by helicopter (see photo). They, too, ended up on U.S. Navy ships. The ships became so crowded that the sailors began throwing the helicopters overboard. The war was over. The victor was obvious.

Who Ended the War?

There are several candidates for this noble achievement. Of course, there were the Paris Peace Accords, headed by Henry Kissinger, which did not end the war, but provided a convenient facade.

The leading candidate must be the Vietnamese people, themselves. They fought and died, but after years of being overwhelmed by the U.S.’s superior technology, they staged an uprising, called Tet, which demoralized the U.S. and its Vietnamese allies. Within a few years of much reduced fighting, the Vietnamese were victorious throughout the country.

The American troops played a major role in stopping the war. For all the reasons listed above, they had had enough. They didn’t want to fight any longer. Nixon, and then Gerald Ford, did not want to find out what they would do if they were pushed and prodded by the government. “Better to let sleeping dogs lie.”

The civilian peace movement played a major role. Millions of ordinary Americans hated the war, and wanted it to stop. Not only that, but thousands of them hit the pavement in nearly every city in the country. During the fight against the war, 500 universities went on strike. Lawyers found ways to sue, workers went on strike, and unnamed Americans stopped troop trains.

For years, I believed it was the soldiers who put an end to the war. But recently, I encountered people who assumed it was the civilian non-violent marches and other tactics that were responsible. I guess it all depends on what part of the machine you are attacking. I have no doubt that the Vietnamese fighters could make cogent arguments about how their resistance forced the Americans out of the country.

Now, it seems to me that every hand raised against the war struck a blow for peace. If only our unity had come sooner. If only they hadn’t murdered JFK. If only these horrible people who ran – and still run the country – were not in charge.

At least for 16 glorious years, from the end of the Viet Nam war to the beginning of the Gulf War, there was no fighting to speak of. In fact, the media at the beginning of the Gulf War talked incessantly about how the country was finally breaking through the pacifism of the preceeding decade and a half. The media ballyhooed the imminent beginning of the Gulf war, as if it were a good thing. If only the Viet Nam coalition had stuck together and made continued peace the highest priority.

Unfortunately, people get old and tired, and people die. Fifty years later those heroes who said “no more war” are getting old and dying. Many of them were inscribed on the Viet Nam wall in DC. There should be another wall for those who survived, whether soldiers or civilians, and Vietnamese, too. They are all heroes who stopped a huge war and created peace for another 16 years.